The Golden Age: Recollections from a Childhood in Fourth Ward.

by James Alan Stenhouse. (Story submitted by Ken Kneidel, son-in-law of James Stenhouse.)

Background: Ken’s father-in-law grew up in the Fourth Ward just before the turn of the 20th century, who lived on the corner of Pine and 8th. Jim Stenhouse was the 1st president of the Mecklenburg historical association in 1952, and also authored 2 books on local history: Exploring Old Mecklenburg, Journeys into History.

Preface

This is a compilation of notes written by James Alan Stenhouse about his life as a child in the Fourth Ward of Charlotte. Although born in St. Louis in 1910, Mr. Stenhouse spent his life in Charlotte. His ancestors in fact were longtime residents of Mecklenburg County, his parents just briefly being in St. Louis when Mr. Stenhouse was born. His great-grandfather Richard Stenhouse and his wife Agnes emigrated from Scotland to Huntersville, Mecklenburg County in 1850. Richard Wearn, his maternal great-grandfather was born in England in 1798. He and his wife came to Mecklenburg in 1837.

Mr. Stenhouse was a noted Mecklenburg historian. He was the first chairman of N.C. Historical Sites Commission, appointed by Governor Umstead in 1953. In this role, he traveled over 3,000 miles to record more than 700 historic sites in North Carolina. He also co-founded and became the first president of the Mecklenburg Historical Association in 1954, and was named president emeritus in 1963. He was the first chairman of the advisory committee to the General Assembly on N.C. Historic Sites and first chairman of the James Knox Polk Birthplace committee, both appointed by Governor Sanford. He was a preservation officer of N.C. historic sites for the American Institute of Architects, President of the Society for the Preservation of Antiquities, a charter member of the Historic Landmarks Commission in 1973, and president of N.C. Archaeological Society. In the mid-1970s he won a rare American Institute of Architects Fellowship for his work in preservation.

In addition to his leadership in the above organizations, Mr. Stenhouse has authored two books on local history, Exploring Old Mecklenburg and Journeys into History, both published in the early 1950s. Mr. Stenhouse was an architect and co-founder of J.N. Pease Associates in Charlotte. His interest in buildings and construction began early. He won a city-wide drawing contest when 13 with his sketch of Guthry Apartments under construction at the time. Also as a teenager, he constructed a scale model of the buildings along Trade and Tryon in the downtown of the 1920s.

The following was written from 1993 until his death in November 1996 as he remembered a Charlotte quite different from what we see today. – son-in-law, Ken Kneidel

Introduction

One hundred and fifty years ago, Fourth Ward’s fate was decided by the railroad which avoided cutting it in two, going around instead. Charlotte was planned around the crossroads of Trade and Tryon streets, Tryon running north-south. These roads divided the circle into four quadrants called wards. Northeast was First Ward, the southeast was Second, southwest was Third, and northwest was Fourth. The Fourth Ward became a residential neighborhood when the railroads came through, as Charlotte’s other three wards declined into railroad yards and blighted areas. It has not expanded beyond its original bounds. It is much like a walled city.

The early years of this century were golden ones for Fourth Ward and I’m glad I was there. It was the choice residential area of Charlotte, with many fine houses and residents who knew how to live the gracious life. Some were wealthy but certainly not all; wealth was never mentioned, never shown. Some houses were large, some small, some close to the street, some far back, and the large elm trees were spaced in a random manner. The long straight streets of white crushed stone were beautiful in the sunlight and shadows. A horse and carriage would move silently by. People would wave and speak, their friendly manner providing the hallmark of the grand cheer of the age. The neighborhood had a casual informality caused largely by the houses of various sizes. The large elms kept the area in mostly shade, but sunlight in patches on the white stone streets was beautiful at midday. The houses were different, but all in the Queen Anne style of fancy lace-like woodwork on gables and porches. All houses were of wood with a slate roof and some had a round corner tower with a conical roof. There being no air conditioning, houses had porches of one, two, or three sides that made delightful places to cool off, sit in a rocker, and talk. The streets of sand and soil were the color of the beach and were ideal for the play of jump rope, marbles, running races, or baseball. In my yard, we played in my treehouse, and also with horseshoes, see-saw, and swings.

Everything was so different. There were no automobiles and no one wanted one. The men could easily walk the four or five blocks to work uptown and the ladies of the house put on their floor length dresses to have tea or shop at the trader’s wagons that would come to show their wares. There were no shopping centers or even a grocery store, for the ladies had no way to get to a store. They walked in the clean white sandy streets by the line of wagons, enjoying very much the company of the attractive young men who were the merchants. The young men enjoyed the company of the buyers and sat and had tea and cookies at the yard tables. Little boys rode their stick horses, shooting and playing cowboy in the street and the girls played with their dolls.

Even horses and buggies were seldom seem for they were so much trouble unless you had a coachman. If one was necessary they could be rented at the Ward livery stable on Fifth St., but this was trouble too. The doctor came in a buggy, of course, because getting to him was too difficult. There were many other services. The Paddy Wagon would take you to jail. The Fire Wagon went to fires. The Dray would haul your trunk to the rail station, the Ice Wagon, the Milk Wagon, Berryhill’s Grocery Wagon, The Fish Wagon…..a wagon for everything. Still there was almost no traffic of any kind. The streets were safe for play.

My Family

I was raised largely by my mother, grandfather (“Papa”), and grandmother (“Mama”). Papa was about seventy-five when I was five, but we had a fine relationship, although we were as far apart in thinking as in years. I remember him well staring at me over our kitchen counter with that blue unblinking eye. He had a glass eye that he left on the counter every night, and a glass eye really seems spooky — especially to a three or four year old.

I sometimes made toys that looked dangerous, even when they weren’t. One that I made was a model of a steam-driven concrete mixer. In those days everything was steam-driven. I fired it with a mixture of coal dust and kerosene. It was about the size of two cigar boxes and wasn’t very dangerous, but Papa didn’t ask my opinion, he just said as he went uptown one day, “If I catch you playing with that again I will destroy it.” I must have had some devil in me because I found myself wondering if Papa was a man of his word. When it was about time for him to come back I started up the fire in the boiler and got right on the walk where he had to see me. Open defiance. As he approached I wondered if I would get by with a lecture on what a concrete mixer would do to me if it blew up. He walked rapidly, his leg came back and I knew. Wham! His foot hit it squarely and away it went through the trees, trailing smoke behind. He never said anything and neither did I, but we understood.

Mama was quite a girl when young they say. Papa met her in Kentucky when he was editor of a small newspaper there. She was one of Kentucky’s best horse-women and an excellent shot with a gun. She could hit a can with a pistol when riding at full speed. Whenever I did something bad my mother took me before Mama who would judge the case. She always sat in a high-backed chair like in a throne, with her elbows rested so that as I stood before her to the side, she could let her arm fall and knock the top of my head with her heavy gold ring. I had no complaints. In the usual case, there was nothing I could say. If I had chocolate on my face and had been told many times I could not eat candy before dinner, the judgment was quick. Mama looked like a queen in that throne chair.

My House

My house was in the exact center of the Ward at the corner of Pine and Eighth street, just across Pine from the Overcarsh house, which has become prominent and still stands today. Ours was not quite as elegant, our family fortunes at the time being very low on both sides. Our house was actually a very, very cheap little shanty, the only rental property in the neighborhood. However, no mention of any difference in wealth was ever made and I wonder if it was ever thought about. Children of course never give status a thought. But we were poor, there is no question about that. It may have had an effect on my future behavior, but not while I lived in Fourth Ward.

Stenhouse Home

In summer the kitchen was hot enough to cook the food without putting it on the stove. One who could take the heat was Maybelle, our cook who worked for nothing except her food. We raised our own so we had plenty and May cooked it all day Indian fashion. She came early, built a fire in the big kitchen stove, and put on the grits. Her food certainly did taste good. May lived in a black neighborhood beyond Seventh Street. She worked all day just for food for her and her two kids. We ate at the kitchen table. Of course, May didn’t, this would have been out of the question in those days. I hated to see her going home at dusk. Our house was set up on piers so cold wind blew right up thorough the floorboard cracks and we had no rugs. The ceiling was of boards too, with cracks to let the cold come down. There was no insulation of course. The windows were loosely fitted, letting the cold wind blow from the sides. There was no furnace and we had only small coal-burning grates. At night the temperature inside was the same as outside. Water in a bowl and pitcher on the bedroom stand froze solid. The only place to bathe was in a zinc tub set beside the kitchen stove. There was no heat in the toilet room. The wooden roof shingles curled up and rain dripped all over the house. The water pipes under the house froze and that meant crawling under the house with a torch to thaw the frozen pipes. On cold days everyone sat in the kitchen around the big cast iron cook stove. Our old hound dog slept under the stove.

The yard was in keeping with the shanty. The front and side were only about ten feet from the earth’s sidewalk. The street too was unpaved, and this level dirt continued on under the house. There was no grass and no shrubbery. It looked like what it was — a very cheap shanty. Today the law forbids human habitation in such a place and well it should. Although my grandfather wore folded newspaper in his shoes covering the holes, and I got only one toy for Christmas, I never complained and fully realized that we would just have to tough it out. In 1923 when I was thirteen my house was destroyed by fire as the golden age passed.

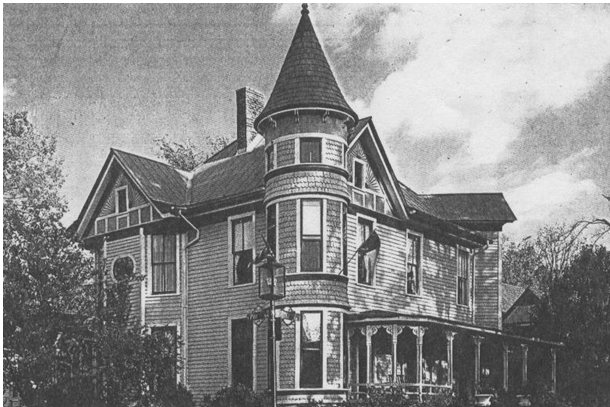

The Overcarsh Property

The home across the street was another story. The house was built in 1870 and was inherited later by the Overcarsh family. It is a large two-story Queen Anne house with a round tower on the corner and porches across the front. The smaller porch on which the front door opens is only six feet wide and only four feet from the sidewalk, even though the lot depth is ample. Chains lined the narrow porch, where people rocking in chairs would speak at length to neighbors out for a walk. It was not only a pleasant thing to do, it was the only thing to do. There was no entertainment to go to and none at home, but when there was a gathering of neighbors, there was plenty for all ages.

OverCarsh home

The Overcarsh family had two teenage girls and two boys, an attraction for all. At parties, visitors brought guitars, banjos, and mouth organs to the large porch which connected to the long narrow one. A big swing held some as teenagers went to the kitchen to make candy. A few couples would swing in the grape arbor under the quarter moon, while the kids played ball under the corner street light.

Their son Albert and I were born only two days apart and in recollection, it seems that we played together every hour of every day for twelve years. Most boys would rate their mother first of personal influence, and so would I, but I also had something rare in this regard, with Albert, the perfect playmate next door. We never said a word in anger to each other, and never had a disagreement.

In front of the house was a square lawn with a fountain and a small pool in the center where Albert and I played on very hot days. On the back of this lawn were arbors for four types of grapes, and several different types of fruit tree, including pear, apple, and quince. The back of the house was a big chicken yard. Chicken meat was popular because it was about the only meat! Beef could be had at the Berryhill Store at Pine and Ninth, but it was very costly. My father hunted and we gave Albert’s family some rabbits plus vegetables from our big garden in exchange for some chicken meat and eggs.

It’s an odd thought today, but the pattern of living in Fourth Ward was controlled in part by insects. There were many flies because everyone had chickens and other animals such as goats, cows, turkeys, or ducks. And there were horses in the streets and grape arbors and fruit trees dropping fruit to rot. There was no garbage or trash pick up, no pick up of dead animals. The biggest attraction for flies was scrap food put out for chickens. The flies loved this.

As a consequence insects had to be considered when the Overcarsh house was laid out. The long narrow porch on the front was only six feet from the sidewalk, yet the property was deep enough to have been moved back fifty or sixty feet to create a large front lawn. The reason why was simple. A light inside at night attracted bugs, so everyone was forced to sit on the porch in a row of rocking chairs facing the sidewalk. Being forced outside, the only logical thing to do was to put the house close to the street. This allowed for a running exchange of gossip with neighbors out for a walk. Although screening was in use in the country since 1862 there were no window screens in Fourth Ward to keep out the insects.

On rainy days Albert and I worked in the shop in Albert’s yard. What a great place to be in the rain! A big window on each side gave us plenty of light and the rain played constantly on the tin roof. The shop connected to another building for wood storage and also to the hen house. Occasionally, one of us would slip in the back porch door to raid the cookie jar. I feel sure that Al’s Aunt Kate in the kitchen heard but never let on. She had no children of her own, but she understood. Al would often hide behind her dress when he got into trouble. She was small, thin, quiet, but happy. I guess Al and I would not have been able to play so hard if she had not been of a notion to give us cookies.

Albert and I were very good at building things. We made a race car in which we could coast downhill. There was one trouble in the workshop, our dogs always seemed to want to curl up and sleep right where we wanted to work. No matter how much we yelled at them, they’d never move or even wake up. But they’d wake when a ripe pear dropped on the metal roof! I certainly was glad Mr. Overcarsh lived here because he had a lot of good tools for us to use, and was so open to our using them. He was so nice, and he liked tools too. Never did I see him in a bad mood. He was a little man who was forever bouncing around fixing things. He carried a tack hammer all the time in his back pocket, looking for something to fix.

James Alan Stenhouse

A Child’s World

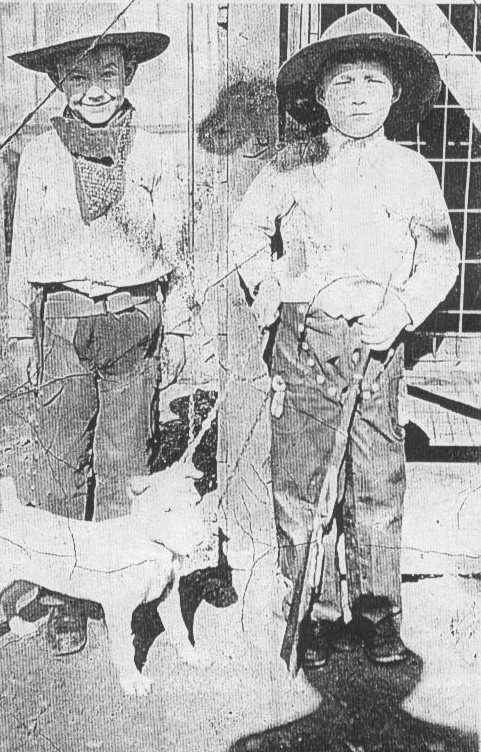

Cowboys — It seemed that several times a week some mother would have a tea party for neighbors and girls. The girls would dress up and take their dolls. The women and girls liked to talk, but the boys and men liked to play cowboy. We had complete outfits with chaps, shirt, two pistols, cuffs, hat, rifle, and black licorice for chewing tobacco. We rode stick horses made from broom handles with a toy horse head nailed on. Many days we played cowboy all day long and into the night by the campfire. We cowboys always carried at least one pistol ‘cause there was always a chance of meeting a stage robber. We had a billy goat wagon on which we built atop like a stage, and sometimes we were the robbers and held up the stage. Sometimes the billy goat was the horse. If only he would have acted like one!

In the center of the square block in which my house was located was a hay barn that provided a great opportunity for some fun play. No one ever objected and we did no damage. It was much fun for us cowboys to shoot a robber out of the loft and have him fall into the hay pile at ground level. Western motion pictures of this era, with Tom Mix and Hoot Gibson were heroes to the little boys of Fourth Ward. The little movie theater, The Ideal, was just wide enough for eight seats on each side of the center aisle. When the little cowboys got seated the shooting started. Under the screen were the piano and the player. The music was exciting, but hardly overcame the yelling of the cowboys in the audience.

Secret club — Pritchard’s porch in the darkWe had a secret club that met in a place that was just dark enough to be spooky at night, but not so dark that the faint-hearted Indian brave might not show up. It was the side porch of Dinky Pritchard’s house, which was only half a block down Pine from the Overcarsh porch. The principal business of this club was to tell ghost stories. Where the porch attaches to the side of the house a simple board bench sat against the house. The Indian chief would sit on the left end and any new member would sit on the right. On the right seat, we cut a small hole and rigged up a needle that would move upward when a string under the board was pulled on the other end by the chief. The chief would tell a good suspenseful Indian story up to a point when all was quiet, then he’d reach down and pull the string. The little new member would yelp as he shot upward holding his rear!

Tree Houses –-Across little dirt Pine Street from Albert’s back yard, I had two big mulberry trees in my yard that were perfect for climbing, and kids everywhere knew about them. It seems that there were always about two climbing the trees, about two coming down and about six just playing in its tree house, about ten feet above the ground. These trees were so special because the bark was smooth and easy on bare skin, and there were so many holes to hold on where little limbs were broken off. They also had just the right number of limbs at the right angles to make climbing great fun. One of the trees near the street was well known for being totally hollow, even in the high limbs. Any talking into a hole where a limb had broken off could be heard in the big hole at the ground. The most fun was to put smoking rags in the bottom hole and see the draft take the smoke out the limb holes. Riders in wagons on the street would stare in amazement at the smoking tree, all to our delight.

Our little dogs, Spot and Tyge cried to follow us up so we made a pouch in which they could ride on someone’s back. Tyge was scared being lifted, but he was really glad to be in the treehouse. He wagged his tail so violently I was always afraid he’d fall out.

Memories of a haunted house — On West Fifth Street, then called Cemetery Avenue, there was a deserted old mansion that was empty and haunted. It was just west of old Settlers Cemetery hidden from the street by huge magnolia trees that made deep shadows. We boys would creep around the yard of this old house, being, as we were, hidden in the deep shadows of the magnolia and almost overcome by the heavy sweet smell of the big white blossoms. The smell of the dead!

James and Albert

Peeping in the high windows of the mansion one day we saw a lavishly decorated interior, just as if the owner, now dead, had only left briefly, soon to return. I remember returning to our treehouse and talking in low tones, as is always done in a conspiracy or when dealing with ghosts. We decided that the next day we would all go back to the haunted house at night. All five of us walked in the light of a full moon. I remember our terror and panic when we saw something pass in the house through the moonlit window. As quick and quietly as possible we ran out onto North Poplar Street and then home.

No one would believe our story as we breathlessly told it, but we know today that we did see something move (I did at least). Three blocks west was a cemetery with many upright headstones of white marble. On full moon nights, we ventured down there to see the ghosts that people swore on the Bible that they had seen. Later I found out the answer to this mystery. The ghosts were probably, harmless tramps. There were many tramps in those days and they slept in empty houses and the cemetery often. They slept there because the railroad police shooed them away from nearby railroad property.

Chores —Albert’s house and my house both faced south, from the north side of Eighth St. and were across Pine from each other. Thus, our back yards were across Pine from each other, and Albert and I could lump our chores as one package and do them together. In the beginning, this didn’t look very good because it looked more like a mountain than a package. We both agreed that we should do some chores, but not so much!

We had to pluck chickens, cut the grass, sweep the porch, and pick pears, peaches, and grapes. In addition to hoeing and weeding the garden, I had to pluck the chickens, skin the rabbits, scale the fish, cut them open, clean them out, nail up the skins to dry, and put the heads and feathers on the trash fire. This was the source of that pungent odor that permeated Fourth Ward quite often. I think the first feather pillow was made when some guy stuffed a bag full of feathers to keep from having to burn them. This messy procedure went on at all houses. We had to feed everything on earth it seems. The chickens, the turkeys, the peacock, the rabbits, our dogs, and the cat. We always hoped for rainy days when the mountain of chores seemed too high.

My Mama always said that I should do these chores without being told, and to be honest, she had a point. But I did too. If we did things without being told, they’d be sure to think we didn’t have enough to do. We hoped that by having them tell us twice, it would sound like we were doing twice as much work as we really were!

As a child, I had to work to make money too. So I had many jobs, such as selling newspapers on the street. I sold perfume in the neighborhood of Fourth Ward between Seventh and Trade Streets. I packed fruit. I painted on construction jobs. I did anything to make money. Door to the door I sold Easter egg dye, needles, cookies, Christmas cards, Easter cards, birthday cards, light bulbs, Christmas cards, toilet paper, salt and pepper, matches, soap, candles, aspirin, gum, and hair straightener.

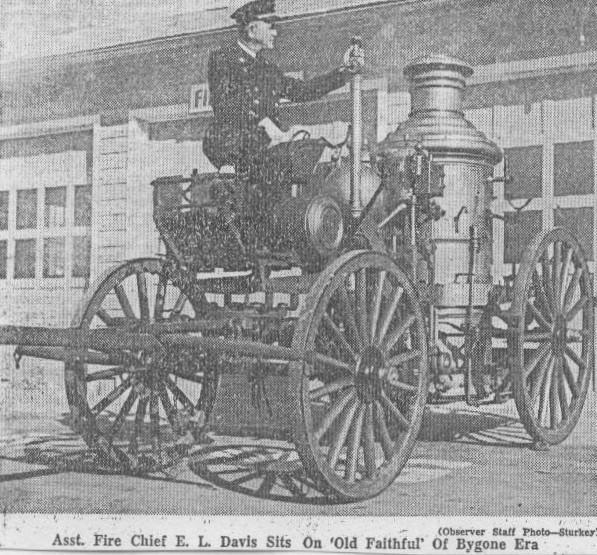

Fire, Water, and Steam —Fourth Ward’s Police and Fire Departments were in the city hall on Fifth Street. Children could almost always be found on Fifth Street across from the big doors to the firehouse. Buildings were not required to be fireproof and fires were far more frequent than today. Wiring codes were also lax. Many a vacant building has been burned by rats nibbling wires, not in conduit.

Steam engine in 1903, Charlotte

We kids often sat with our dog across Fifth Street from the fire department to watch the call to a fire. The bell would clang and firemen would jump wherever they might be. Those upstairs would slide down brass poles. Those closest to the horses would throw on the harness and lead them out of their stalls. These huge fire horses would have been through this routine many times and would know what to do. A match would light the set fuel in the boiler just as two horses would slip into the harness. Firemen would jerk on boots and fire coats and black fire hats. The chief dressed all in black too, except for his red hat with “chief” on it. He would step up to the driver’s seat on the steamer and take the reins. The most exciting piece of fire-fighting equipment ever made was the steamer. A silver-plated vertical boiler sitting low between big wheels. With a loud yell “Go!” they’d roll from under the smoke and head for the turn at Tryon. The huge six-foot-high back wheels rimmed in steel would begin a spectacular sideways skid over the cobblestones sending out a shower of sparks in black smoke.

What a thrill for little boys! The captain sitting high with the driver was the envy of everyone. Two firemen would stand on the back step by the boiler holding onto the grab bars and clanging the bell. The firehouse dog, a spotted Dalmatian, would run along behind as fast as he could.

Four blocks to the south was another steam wonder, the fire department’s steam pumper, which put on a show once a week, pumping a stream of water far, far into the air over the cemetery. This was a vertical boiler that looked like a bottle underslung between big wheels to make it stable. The front had a pair of smaller wheels, a driver seat, and two big white draft horses. The steam pump was between the boiler and the seat. In action, a large horse ran from the hydrant to pump, and four smaller hoses came out the other side. Smoke, steam, and sparks shot fifty feet up in a roar, and water from the hoses went as high. We kids stood transfixed and watched the steamer practice every month on West Fifth Street by the old Settlers Cemetery.

The water tank at Graham and Fifth Street attracted us because it was one of the tallest structures in town I believe. The tallest office building was twelve stories. The “standpipe”, as it was called, was somewhat of a marvel and was only four blocks from our house, so it was a natural attraction. I can remember standing about five feet from the bottom on the Fifth Street side and leaning back to look up to the very sky. The big steel plates were riveted into a huge pipe which stood on end — thus a “standpipe”. The plates overlapped and the rivet heads were about one and a half inches around and four inches apart. The steel came down to the concrete at grade level. It was painted a bluish medium gray, just like an ocean-going ship made of steel plates the same way. High tanks give good water pressure and this tank was on the highest ridge around. There was a ladder to the top, but I never heard of anyone climbing it. This was one of the last standpipes ever erected. All tanks today are up on legs. The site of the standpipe is now a parking lot. The foundations are no doubt under the asphalt. In old skyline pictures of Charlotte, the standpipe stands out.

Another attraction was four blocks to the north at the Seaboard railroad near Twelfth Street. Here the greatest excitement would come when the world’s largest steam (Mallet) locomotive came into town after a dash from the coast at sixty miles an hour, pulling 150 fully loaded cars of coal. Sixteen drive wheels, four steam chests, two smokestacks, a sight to never forget! This mighty giant, steaming, smoking, shaking the earth with its weight as it rolled slowly by, left us boys entranced. It was twice as large as any other locomotive ever built. Every day at four o’clock we were there to watch trains. The proud engineer always waved out his cab window to us. Occasionally this giant stopped for refueling — 30 tons of coal and 30 thousand gallons of water. Starting forward again was the big show. As the mighty Mallet strained, steam jetted smoke high into the air, and jets from the steam chest spurted twenty feet to the sides as the wheels began to slowly turn. Thus, with much hissing and roaring the monster would begin to move as at least half the little boys and the dogs ran away as fast as they could.

Mr. McGinn of Fourth Ward was a conductor, the man who was the captain of the train, but the man admired the most was the engineer, who drove the huge locomotive. He was the father of my playmate, George Jones, and one day he let me climb the steps into the cab and sit in his seat beside the window. The seat on the other side was for the fireman, whose job it was to shovel coal into the firebox. He opened the door so I could see the white fire. This was a thrill, looking into the mouth of the white-hot firebox. The railroad was right, this was no place for children, but nothing could dampen the thrill of steam.

The baggage car of a train was a very busy car in those days. Travelers of that time usually took a large trunk with them even on short trips. Those big wardrobe trunks were at least four feet high and opened vertically, so all clothes hung on a hanger. The reason may be that textiles then wrinkled much more easily than they do today. But, be that as it may, Mr. Blackwelder who lived in the house adjacent to Albert’s on Eighth Street was a baggage master on the railroad. He often invited Al and me to take a ride in the baggage car. What fun! The car had an eight-foot-wide side door that stayed open and we’d sit on a little trunk back a few feet from the door. Sitting there watching the whole countryside flyby is an experience not ever to be forgotten.

All little boys like to watch building projects I believe. I know that I did. It was certainly different from now. There was little in the way of equipment. No bulldozers, no backhoes, no ditch-diggers, no tractors, nothing except steam-driven steam shovels and steam rollers. Steam was the only power. In Fourth Ward basements were dug with a scoop pan pulled by a mule and guided by a laborer. It was similar to a wheelbarrow with a cutting edge on the front instead of a wheel. When full, it was dragged up a ramp and dumped on a pile which was shoveled into a wagon by two men. There was no concrete plant, so concrete was mixed on the site and the use of concrete was limited.

I remember when a gas line of eight-inch cast iron pipe was laid down Pine Street by a labor gang of about fifty men. They often would sing as they worked together. All picks were raised in unison and dropped with an “ump.” The water boy was constantly being called for his bucket with a dipper, a different one for whites and blacks. When the pipe was laid and the workmen quit for the day I got down in the ditch to inspect each joint for leaks. I remember finding a leak and striking a match to be sure. A flame over a foot long spurted and the contractor was called.

Food and Wares

Mr. Berryhill’s Store — We little ones made regular pilgrimages down Pine toward Ninth where Berryhill’s Store stood as it does today. Mr. Berryhill paid no attention to us as we came in several times a week to spend one cent each on candy. Berryhill’s store was the only store in Fourth Ward and was only one block from my house. I went there every time I got my hands on a penny. He had a long candy counter and it took time to see all the different kinds. Some kinds I might have looked at five times before I let that penny go. I wasn’t wasting Mr. Berryhill’s time because he never got up when I went in. He didn’t need to get up to wait on me. I could just take my choice over to him when I finally made my decision. He never had to give me any change because I never had more than one penny. He knew that the clock hands had a way to go before I decided where to place my money, so he just sat in a chair by the front door reading the paper while I made my decision. I really think that sometimes he went to sleep while I looked. It was hard to decide. If I bought a stick of peppermint, that meant I couldn’t buy any chocolate! I know Mr. Berryhill didn’t make much money off me, but I think he did like me a lot and I liked him. He didn’t need my pennies anyway, he lived in a big pretty house catty-cornered across the corner from the store.

Mr. Berryhill was an easy-going man. He sold canned food, beans, flour, meal, salt, sugar, cured ham, etc. The most popular was beef. His big freezer had a whole side of beef which provided a change from our usual rabbit and chicken.

The Mule and the T-Model — Mr. Berryhill once tried delivering groceries, but the experiment did not work out well. His friends were divided as to the merits of the mule, but Mr. Berryhill bought one and a light delivery wagon. He had a kind heart and he did not want to have a big wagon for the mule. He didn’t know that mules are very stubborn and contrary beasts that won’t move when they decide not to. Well, that’s the way it was with this mule. He often balked enough to make the driver lose his patience. One day the driver lost his calm and when the mule would not move he got off the wagon and gathered some dried weeds which he put under the mule’s belly. Then he struck a match and lit them. The mule only stepped forward until the new wagon was over the blaze. Two laughing men quickly slid the wagon sideways.

After this, Mr. Berryhill decided that a mule was out and that he would get a T-Model Ford. It couldn’t be any worse than a mule, nothing could be worse. A young black man named Amzi was looking for a job and asked if he could give the T-Model pick-up truck a try. The truck was about four feet square. Over the seat was a canvas top. The engine was so small that one man could keep the truck from moving with no trouble. Of course, T-models had no starter, no gears. If a stop was to be for, say thirty minutes or less, the engine wasn’t cut off. It just sat there and chugged like a lazy old hound dog. It could be started only by cranking and that was dangerous because of the kickback. Men with broken arms because of this were common. Often the T-Model would run over the man cranking and he would get up and chase it down the street.

When Mr. Berryhill’s T-Model was left like this the Ford had a tendency to drift slightly forward. To keep it in place they decided to use a horse weight that Amzi dropped out like an anchor. The little engine was not strong enough to drag a weight. Even with the weight, Mr. Berryhill still felt uneasy about leaving the truck unattended while running. He asked me if I would like the job of sitting with the truck to watch it while Amzi took groceries into houses, and I said sure. I felt like a fireman or something sitting there behind the wheel while it ran. Girls admired me. Boy, this was some fun. Others were curious because few had ever even seen an automobile.

Our Garden — The house to the west of ours at Eighth and Pine was Mason’s at Eighth and Graham. Most of the space between our houses was Mason’s pasture where they had a cow for milk, but adjoining our house was a big garden. We had more than we could eat. The Mason’s boy Lowell was my senior by several years, so we were not playmates but acquainted. He later became a quarterback at Duke. We played ball in the pasture and no one minded, not even the cow, but I learned not to run across the pasture full speed on a dark night. I ran into a sleeping cow one night. For a few moments, I didn’t know what had happened and I guess the cow felt the same.

We planted some of everything in the garden and traded with the Overcarshes for eggs and chickens, which they raised so they could trade with us. My dad got rabbit meat by planting carrots on small mounds and as the rabbit below the surface pulled the carrot down my dad would fire his shotgun at the mound to kill them. We planted extra carrots for the wild rabbits and it worked fine. If we shot more than we needed we traded them for eggs too. Many vegetables were canned for winter eating.

The Pine Street Market– Wagons brought wares to the homes of people on Pine Street. Early on a summer morning, Pine Street would be shady and cool under the great elms as the first wagon would arrive. It would be a morning of shopping for housewives and young ladies of Pine Street, but they would make no chore of it. They would dress for what became a twice-a-month party. Coffee and cookies would be served at yard tables. Shopping and gossip would be at its best. The ladies knew the merchants, some of whom were not only young but attractive.

The wagon I liked best was the toy wagon. I liked broken toys best because I liked to fix things. One day I noticed tossed in a corner as though thrown away, a doll about a foot long that had a broken head with a piece missing. I asked the man about it and he gave it to me as I hoped. In Albert’s shop, I found some plaster from Albert’s broken leg and I patched the hole and painted it. Then I washed it and the dress. I wrapped it in a paper and when the toy wagon came back I gave the doll to the man and asked him to give it to some little girl who had no money but needed a doll to love.

The book wagon had children’s books that my mother and Albert’s mother got together to trade for. Children’s clothes were popular purchases too, for some were out-grown before fully used. Of course, the pie and cake wagon was one I especially watched for. A buy there meant I could look forward to some good eats. I really got excited over the ice cream man, who rode a bicycle with a box on the side. He sold small cones for one cent. That price was in my range.

The Ice Wagon — The ice wagon was different. It had a big wooden box with big blocks of ice in it, four feet wide, four feet high, and six feet front to back. The floor, on which were several very large blocks of ice, was three feet off the ground. The iceman would stand on a wide step at the back to break the big blocks into smaller ones with an ice pick. Pieces were usually about 25 pounds. Each house had a set of printed cards and the housewife would hang out a card showing how many pounds she wanted. He’d just break off the right size and carry it in with his tongs and put it in the icebox on the porch, not necessarily disturbing anyone. This was the wagon that barefoot children waited for on a hot day, for they could stand on the step and get ice chips to eat. There were always piles of chips that we were welcome to and the happy ice man always laughed at the way we went for his scraps. Children also followed the wagon to get chips. Our iceman was a jolly man and he got as much pleasure out of watching us as we had following him.

The Milk Wagon — The milk wagon was a small white wagon with no seat. The milkman stood all the time, getting out of either side to take in a half-gallon glass bottle to put in the refrigerator, which always was on the open porch of each house. Our milkman had a teen-aged helper, now the world-famous minister Billy Graham. When I knew him in Fourth Ward he was only a bare-footed little boy with a rough job. On a bitter cold day hauling milk was tough work.

Entertainment

An Uptown Stroll — The Overcarsh house is only three blocks from Tryon and sometimes the bunch took a stroll uptown to see what might be going on. There were bright lights at least, and everyone walked in the street. Show windows would brightly light something unusual. Popcorn or ice cream could be bought. It was much like a carnival. A man would walk a tight-rope overhead. On occasion a human fly would climb the new twelve-story bank building as all stood transfixed, motionless as their ice cream cones melted and dripped. Some nights they had fireworks. The one occasion I remember best was the night I did something unusual. Barefooted, I stepped on a red hot cigarette. I went up so fast I could see over the crowd!

Tryon Street, looking southwest

A Lawn Party — I remember a Saturday when we had a lawn party. The first hint that something good was going to happen was during morning tea in the living room, where Albert and I overheard the word “cake”. Our joy was brief because we also heard the words “cut” and “grass”. I started to get up to sneak out, but I saw Mom looking at me. She was a mind reader. We were told to get at the grass quickly.

Then we were told to get the Japanese lanterns from the attic, a really good sign that this was going to be a big party. There were sixty of them. Mr. Overcarsh helped by putting a wire around the side lawn about seven feet high. Then wires were strung that crossed at the center over the fountain. Then lanterns were hung out, candles put in. The ice cream freezers were put between the grass and porch and tables set up on the porch for cakes and lemonade. Then a lot of lemonade was prepared and ice was brought to the porch.

At the party, fiddlers would play for a square dance. For dancing, the women wore lacy dresses that were starched to stand out. The men wore long tight western pants. With the candles all lit and with all the music, and the noise of the caller and people dancing, we couldn’t help having fun. But for us, the ice cream was the best. The girls were pretty and the boys were fun to watch. Many strollers dropped by to see the fun, and many carriages passed also. All were welcomed at the party.

A Watermelon Party — My garden was known for blocks around, but then Fourth Ward was a very close place in which to live. Watermelons were special because when cold they gave welcome relief from hot summer days. Because of this Al and I gave them top priority, giving them frequent weeding and plenty of water in a dry spell. When they were ready to pluck, and if we had a bountiful crop, we’d have a watermelon party. We’d make two tables with sawhorses in the yard near the garden, which was the western half of the yard next to Mason’s pasture. Next, we’d get two zinc tubs, which were Al’s and mine. We’d put the tubs where there was shade all day long, and then cut the melons loose and haul them in our wagon to the tubs and put them in. When the ice wagon came we put a big ice chunk between each pair of melons. A board across the melons with ice on top kept them down when water was put in the tub. Each tub was covered with newspapers, and before long they’d get nice and cold. People from throughout the neighborhood would be invited on a Saturday to enjoy a cool treat and friendly company.

A Winter Night —Sitting before a fire with friends and pets on a bitterly cold winter night was as good as a lawn party in the good old summertime. There were card games for all ages or checkers or any number of games. Sitting in a big circle and telling jokes was big fun. The all-time winner in joke-telling was my grandfather. “Papa” was always proper and starched. Never did I see him relax — even on a holiday. He always wore a coat and tie with a clean shirt collar with a trim white mustache. But in a joke-telling party on a winter night, he could bring down the house and be begged to take the floor. Papa was a member of the Wearn family, which was prominent in Charlotte at the time. The Mayor was a Wearn, the baseball park was Wearn Field. Papa was a retired newspaper editor,…… but back to jokes. The problem with Papa’s joke-telling was that he never, never, got to finish one! He always ended laughing hysterically at his own joke. As he sat there wiping his eyes the whole audience would also be in hysterics, laughing at him. It was always this way and friends always begged and begged for him to try again.

All during the evening, there were hot chestnuts and peanuts and hot popcorn, toasted marshmallows, pickled peaches, and in the kitchen lemonade or cider. There might be singing with accompaniment by piano or guitar. A cold biscuit or two, with cold butter and cold maple syrup or cold honey, then your choice of cold sweet milk or hot coffee. The night would end with hot bricks wrapped in a blanket in the foot of your bed.

Automobiles — race day: Charlotte’s most prominent citizen, Osmond Barringer, lived in Fourth Ward on Eighth Street. He brought the first automobile to Charlotte and opened the first agency. The “automobile” as we know it today was slow to develop. The first ones were more like the buggies they were intended to replace, with the horse simply replaced with a motor. It took a long time for automobiles to become popular because town cars were just too uncomfortable and too much trouble to own and operate. Being in a car still meant riding in the rain, dust, and cold. The tires were poor and tire trouble was certain. Roads were poor too, making driving outside of town very risky. Another problem that people worried about was the very dangerous plate glass windshield. I saw an accident at Pine and Ninth in which the passengers were cut very badly. If the engine stopped it had to be cranked, which some people could not do.

Progress was much quicker with racing cars, however. Their engines had changed substantially from those in the first cars invented, just thirty years earlier. A big speedway was built in Indianapolis and it was very popular. It was then decided by the powers that be, to build three more high-speed tracks with turns banked forty-five degrees. Barringer was one of the powers, so Charlotte got one of them, with the others in Pennsylvania and California. Charlotte’s was built beside the railroad in Pineville. Charlotteans were excited to realize that there would be no faster speedway on Earth than Charlotte’s. On race day, crowds would line the railroad tracks for a ride to Pineville, about ten miles away from Fourth Ward.

It is interesting to note that there would be 40,000 people enthralled with the cars at the racetrack, but of the 40,000 very few would consider investing some of their own money into owning such a novelty. As mentioned earlier the town car was much too uncomfortable and dangerous, not to mention unnecessary, unlike today.

Two shuttle trains hauled spectators to Pineville on race day. In the stands, the excitement was rampant. In 1925 times were good. Most had never seen an auto go over thirty miles an hour, but now they would see what could be done when the serious emphasis was placed on speed. The race cars were beauties. Very thin, just wide enough for a man to squeeze in. The wheels were out from the body to prevent turning over. I have never seen a more beautiful object, far more attractive than the race cars that held two men. Excitement rose sharply when the first car rolled slowly out to the track for a few warm-up laps. The one and one-quarter mile track of wood were almost flat on the straightway, but the turn-on each end was banked 45 degrees, which would accommodate very high speeds. The first lap was for warming up and was generally slow, but it got faster after that and excitement mounted as the cars approached one 100 miles per hour and got higher on the banks. The noise that the great eight-cylinder engines made was deafening, but they still went faster and got louder and higher. They streaked by and peaked at 170 before starting to let off.

The race was exciting and the drivers became heroes. Before the race, the drivers prepared their cars at auto agencies around town and Albert and I visited to worship and watch them. We were all-out race car lovers and made wooden models in Albert’s shop that were sixteen inches long.

A Different Time

Christmas Tree — Christmas started when two or three went out to cut a tree. There was always a big one if it wasn’t put off. The most fun was to decorate it after supper when all were there and a good fire burned in the fireplace. Popping corn would be quickly dipped in red, yellow, or blue vegetable dye and along with some white corn would be threaded on a long strand that would be wrapped around the tree. Strings were dipped in hot liquid wax to make candles. The colored popcorn was brushed with liquid sugar and made into balls the size of a baseball and hung on the tree. Six or eight branches that stuck out beyond the others were selected as candle locations. Then we sat at the dining table and with scissors and paste made colored paper loops, one through the other into a chain that would droop around the room near the ceiling. Then we were called to the kitchen where there were egg nog and fruit cake made by my sister and some friends. Some made ornaments of paper which went on the tree too. Last went red and white candy canes.

Christmas in 1913 in Fourth Ward was simpler than today. Children got only a few presents, but they were good toys, no plastic. A bicycle, tricycle, cowboy outfit, building blocks of wood, fire wagon of steel, jumping Jack, or an electric train.

Fashion — Women’s clothes made a most dramatic change when I was very young. In my lifetime dresses have gone from the floor to well above the knees. In 1912 when I was two I hid under a lady’s dress when we young ones were playing hide and seek at Albert’s house. I could find no place to hide, so one of the young ladies raised her dress and pushed me under among the many, many petticoats.

One of my regular jobs was to lace my mother’s corset. I stood on one leg on a straight chair, putting my other foot on her spine, and pulled the lacing strings as hard as I could until she couldn’t breathe. Before putting on the corset she put on a garment that looked like a slip, except that it had knee-length lacy pants. Her shoes should have been illegal. They were halfway to the knee, had pointed toes, and had at least fifteen buttons that I had to do with a button hook! Then, after petticoats, she put on a floor-length dress. My father also wore button shoes with pointed toes. I hate to recall that I, too, wore buttons. From barefoot to buttons was going too far! It was enough to make me dislike Sunday school.

Hats were impossible. Fruits, feathers, bows of lace — to me it looked like a big pile of trash on the head. The thing that hurt was that mother was a consultant to milliners.

A time gone by —There are other memories like this that help us see how much times have changed. They help set Fourth Ward life in the early 20th century into its proper time perspective. In those very early Fourth Ward days there was a cotton gin only three blocks from my house on Smith Street and Ninth. Eight or ten high-sided wagons piled with cotton stood in line waiting to have their cotton sucked out by a flexible spout from the second floor. In the gin, the seeds were combed out of the cotton. The cotton was then bailed and the seeds sent to the oil mill close by where they were pressed to extract the cottonseed oil. Across Ninth Street from the gin, peanuts were made into peanut butter. Through the big open unscreened doorway, we could see the workers spreading it onto saltine crackers. This was to become the Lance company.

My memory of the Victrola record player that Albert’s family bought makes a fitting end to my story. It shows a time when life was so much simpler and full of surprises quite different from what we see today. That Victrola was the first any of us had ever heard of. It was about four feet high and two feet square. The top lifted for records and sound came out the lower front. Albert and I would sit on the floor facing the screen covering the speaker, entranced. We simply could not understand! Albert’s older brother, B.J., told us that there were little people inside and we believed him. We begged him to take one out so we could play with him.

A note to the reader: Apologies for the abrupt end, but this is where James’ notes stop on life in Fourth Ward. He continued writing up until his death, but mostly about personal matters beyond this point. I hope you’ve enjoyed his personal recollections of early 20th century Charlotte. I find his writing rich with detail and color. There’s no doubt that he was thoroughly enjoying himself as he wrote about this city that he loved.